Over the last few of weeks I’ve focused on philosophical questions connecting movement and self-experience to wider issues. This week I want to return to looking at practical strategies for increasing mobility and awareness. I’m writing partly in response to a question someone recently asked me about increasing range of movement in the shoulder girdle and ribcage, but the approach I’m recommending for thinking about mobility goes beyond any specific structure in the body.

Like most people, when I experience tightness in a muscle or joint, my first instinct is to stretch or shake out that particular part of my body. If I feel soreness in the right side of my neck, perhaps I’ll bring my palm to the top of my head and use it to gently bring my left ear closer to my left shoulder. If my shoulders feel tight, I might interlace my fingers and stretch my hands above my head, or behind my back.

It’s worth noting, however, that while this kind of stretching might alleviate momentary feelings of tension, it is not a meaningful strategy for fundamentally altering our habitual patterns of movement. Indeed, I would argue that if you want increase the mobility of your shoulders, it’s not as productive as you might think to worry about the shoulders themselves.

In order to understand why, it’s worth investigating what is going on when we stretch.

Stretching is a process of finding a position or movement that exerts a force on a muscle - serving to expand or elongate it. This is most commonly achieved passively. We hold a position (like touching our toes) and wait to feel our tissues lengthening. This process can increase our flexibility over time, as our muscles and fascia are encouraged to reorganise in response to the forces exerted on them. However, it’s not always the case that passive flexibility leads to increased mobility (the ability to actively move through a joint’s range of motion). Just because muscles have been elongated, doesn’t necessarily mean that their potential for activation across that new range has been realised. Because of this, many people (notably Andrea Spina) recommend dynamic stretching of the tissues around our joints - where muscles are consciously activated in specific ways during stretching.

Both of these approaches to stretching can be very useful; but I think they are limited by the rather mechanical way in which they tend to focus our attention on individual structures in the body. The human body is a non-trivial system. The relationship between input and output are rarely easily explained. For example, yesterday, I was struggling to balance in a handstand. However, after a few minutes lying on my back and exploring the movements of my hip joints and the twisting of my spine and ribs, I found myself able to balance on my hands with greater ease. I couldn’t really explain how the two explorations were linked, but my experience serves to demonstrate the fact that a problem perceived in one place is not always the result of a problem residing in that place. With this in mind, it’s worth thinking about how the limitation/pain/tightness in one muscle or joint relates not to the joint itself, but to the movement of the body as a whole.

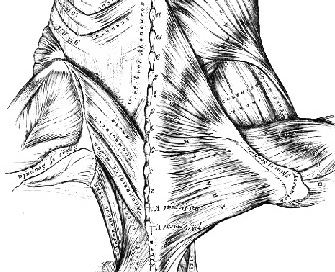

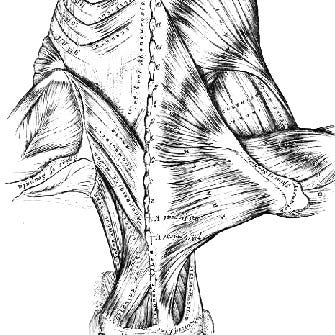

One of the strategies that Moshé Feldenkrais developed to help people move towards a more holistic understanding of flexibility and mobility was to look at problems in a way that might be described as back to front or upside down. In the Feldenkrais Method this is referred to as a proximal/distal reversal - where one reverses the conventional proximal and distal relationships between anatomical structures in the body. For example, we normally think about turning the head in relation to the trunk. When we cross the road we turn our head to the left and right, while our torso remains oriented forward. However, in his explorations, Feldenkrais noted that the same muscles are activated when we (for example) keep the head still and rotate our trunk from left to right. Perhaps more importantly, he found that through turning a movement back to front or upside down, habitual experiences of pain or limitation can be dramatically reduced.

It’s difficult to know exactly why this might be. One theory is that if someone habitually experiences soreness is the neck when they turn their head, they programme themselves to expect pain when they turn. However, this expectation can be subverted by the act of reversal. Because the person doesn’t associate pain with their chest, turning the chest feels safer than turning the head - even though the same muscles are being activated. Through reversing the habitual relationship between parts we can create alternative images of an anatomical structure in the motor cortex, which allows us to experience our bodies in new ways.

This act of reversal is useful in deprogramming some of the habitual ways in which we beat ourselves up for certain deficits. We tend to fixate on the limitations of certain parts and seek ways to fix them. If my shoulders are tight, I worry about my ‘bad’ shoulders, and look for direct ways to change them. However, real, functional mobility is spread across the whole body. It might be the case that shoulders are tight because there is a limitation in a hip joint, which is being accommodated in the lumbar spine, which is being accommodated in the thoracic spine, which is preventing the shoulder blades from moving. Stretching the shoulders might make you feel better for a moment, but it’s not going to address a problem that lives throughout the body.

This is why Feldenkrais said he was not interested in flexible bodies but flexible brains. It’s through addressing the limitations of how we think about our bodies and our movement that the most radical changes to our organisation become possible. So this week’s lesson is about reversal. It’s designed to give you some new ways of thinking about the movement of your shoulders - placing them the broader ecosystem of your body by turning your normal expectations upside down and back to front.

You’ll need somewhere quiet and comfortable to lie down.

This is lovely. In energetic terms, moving the 'opposite' way can restore the flow of life through a joint or area of the body, especially if there is a blockage or something has gotten 'stuck' somewhere. In Laban movement the related term for this is Shape change: allowing each part of the body to respond to the movement of all the other parts freely, without inhibition, thereby restoring lost parts to the Whole. Injury arises when we block Shape change through tension (both conscious and unconscious), and parts of the body drop out of awareness.