This is the tenth weekly Deep Embodiment post, and it’s been lovely seeing the number of readers and subscribers grow. This week, I want to offer another experiential anatomy lesson - returning to the idea that detailed engagement with specific parts of our anatomy has the potential to offer up more holistic insights.

This week’s rather unassuming object of attention is the clavicle.

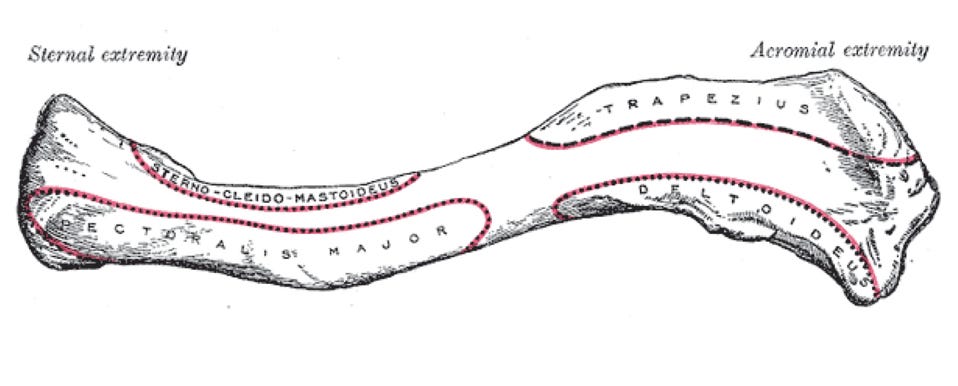

According to the US National Library of Medicine, the clavicle is ‘a sigmoid-shaped long bone’ that serves as a strut between the sternum and the shoulder. Interestingly, it is the only long bone in the human body that is organised horizontally. (It rests in relation to the horizon when we’re in standing.)

I think this idea of the clavicles as a structure that mirrors the horizon as we stand or walk is worth noting, because it explains the rather quiet and steadfast nature of these two delicate bones. Movement in the clavicles is often subtle and small. As our ribs rise and fall with the movement of our breathing, the clavicles remain relatively still. As we turn our head from side to side, the clavicles keep track of what’s ahead. As we move our arms, they make subtle rotational adjustments, allowing the chest and spine to remain calm.

Each clavicle rests between the sternum, where the ribs come together at the front of our chest, and the acromion, a process or bump at the upper part of the scapula. Despite only being about 15cm long and 2cm wide, the clavicles are the only skeletal connection between our arms and our torso. They mediate between the tools we use to manipulate our environment and reach out to the world (our hands and arms ) and the rest of our self. The structure has something of the quality of a ship’s binnacle - the protective housing used to protect the navigation instruments from interference and disruption. The clavicles remain true as the rest of our skeleton twists, inverts or bends.

The quality of the clavicles as a ship’s compass - echoing the horizon, and largely protected from the hustle and bustle of the body’s movement - also has an emotional component. The clavicles remain quiet and constant while other parts of the body collapse and shrink. When we wish to appear confident or proud, we expand across the front of our chest, emphasising the horizontal quality of the clavicles.

Because of their capacity to act as a kind of emotional ‘front’, it’s my experience that lots of people restrict or ignore the clavicles’ potential for movement. (Maybe as a way of avoiding feeling.) When I give Functional Integration lessons, I often note that clavicles are often the parts of the body that are most difficult for students to sense and integrate into movement. Extending the metaphor of the clavicles as a kind of compass, it’s sometimes the case that the mechanism becomes fixed or stuck and true north gets lost. The shoulders become indistinguishable from the torso. The head dissociated from the pelvis.

So while the steadfast quality of the clavicles is part of their charm, it’s also important to explore their subtle and delicate capacity for movement. It’s important to recognise the clavicles as the place where the movement of the spine, ribs and pelvis meets the movement of the arms and hands. The clavicles are where we make concrete yet subtle connections between reaching out into the world and our sense of a centre. If they are finely tuned and balanced, our capacity to move and feel grows. If they are immobile, we lose range of motion in lots of other ways.

So this weeks’ lesson is about feeling and differentiating the fine movements of the clavicles. It’s an opportunity to reset your compass and feel what it’s like when you can find true north.